Turning Residues into Fuel: Why Biomass Matters to India’s Hydrogen Pathway

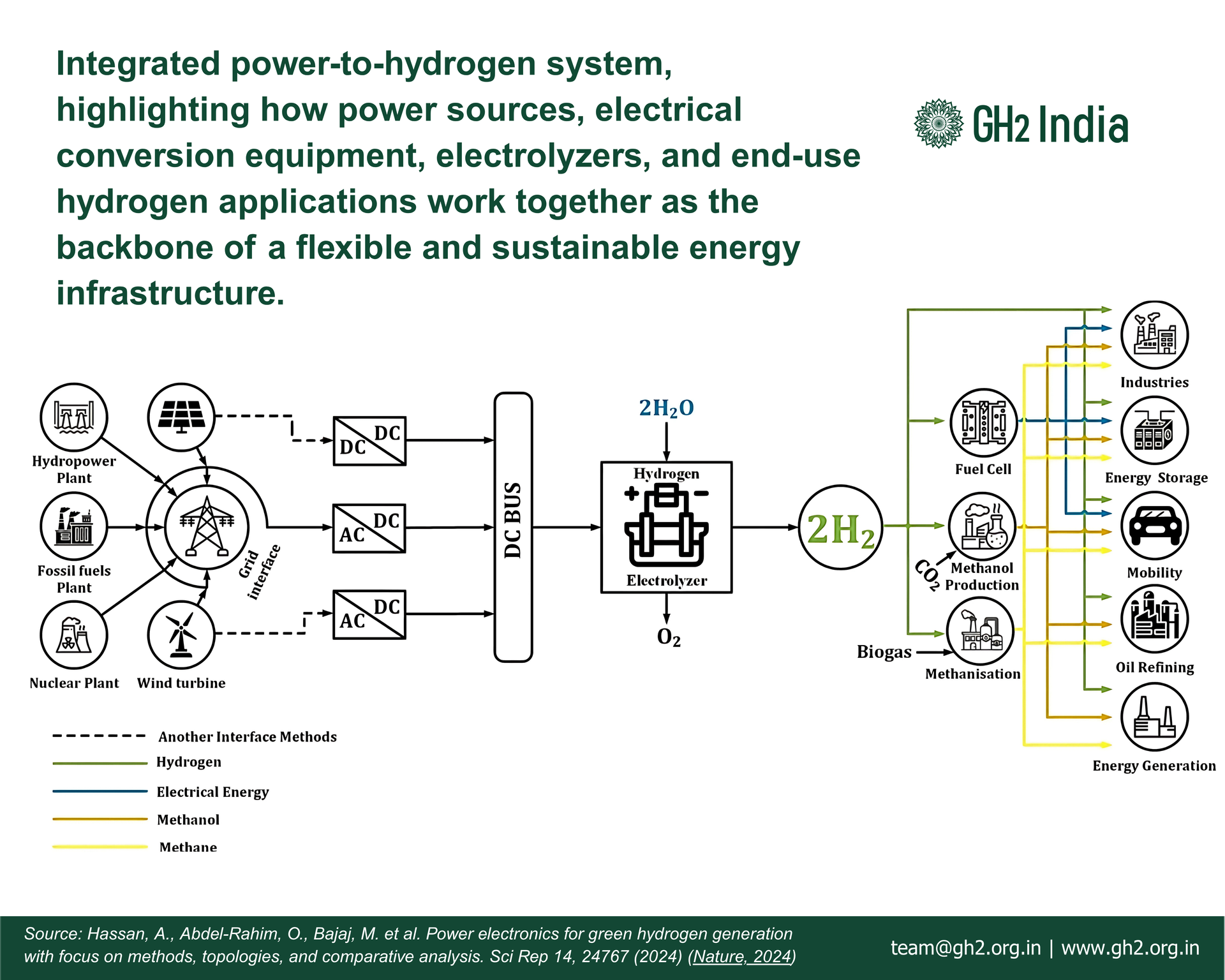

India’s hydrogen transition cannot rest on electrolysis alone. While renewable-powered electrolysis remains central to long-term decarbonisation, it is capital-intensive, grid-dependent, and constrained by freshwater availability. A parallel pathway is therefore emerging, one that is indigenous, decentralised, and rooted in India’s agrarian economy: biomass-to-hydrogen.

India generates hundreds of millions of tonnes of agricultural and organic residues annually by paddy straw, bagasse, crop stubble, forestry waste, and municipal biogenic waste. A significant share of this is either burned or left to decay, contributing to air pollution, methane emissions, and local environmental degradation. Converting these residues into hydrogen addresses two systemic challenges at once: waste management and clean fuel production.

Unlike water electrolysis, biomass-based hydrogen does not primarily depend on electricity. Instead, it leverages thermochemical and biological conversion routes, gasification, dark fermentation, and novel digestion processes to extract hydrogen from carbon-rich waste streams. While these technologies are at earlier Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) than electrolysers and often less energy-efficient on a pure output basis, they deliver something electrolysis cannot: pollution abatement at source and rural value creation.

This makes biomass-to-hydrogen not just a technological choice, but a strategic industrial and environmental intervention.

What the Early Pilots Are Demonstrating

A small but significant set of pilots is testing different technological pathways and business models. Together, they illustrate the diversity and complexity of India’s biomass opportunity.

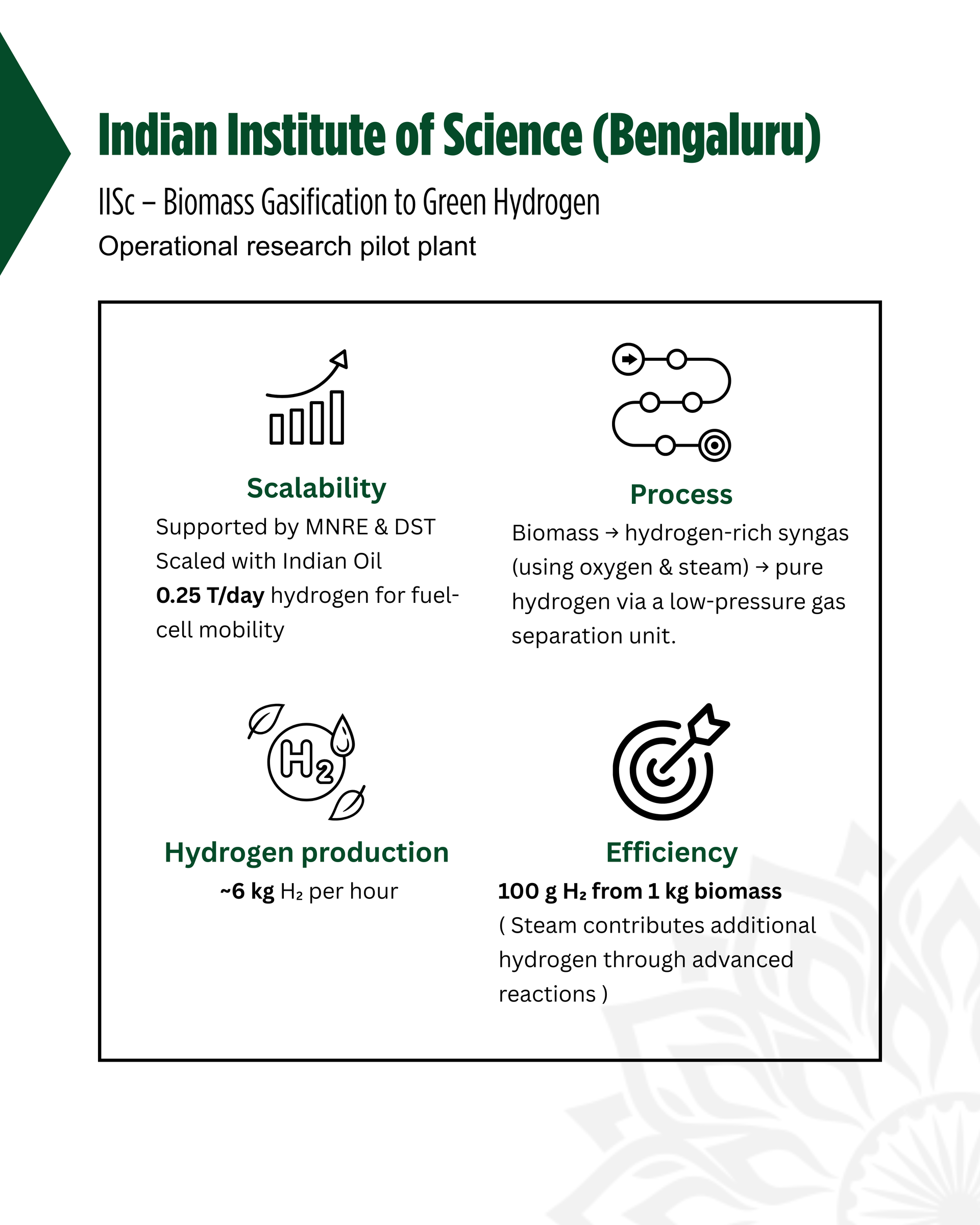

1. IISc–Indian Oil Corporation, Bengaluru

This operational

research pilot uses oxygen–steam gasification to convert agricultural and forestry residues into hydrogen-rich syngas, followed by low-pressure gas separation to purify hydrogen. The plant produces roughly

6 kg of hydrogen per hour, equivalent to about 0.25 tonnes per day, targeted initially for fuel-cell mobility applications.

Importantly, the process achieves around 100 grams of hydrogen per kilogram of biomass, with steam playing a catalytic role in enhancing hydrogen yields through advanced reforming reactions. The project is supported by MNRE and DST and demonstrates how academic innovation can be scaled through a public-sector industrial partner.

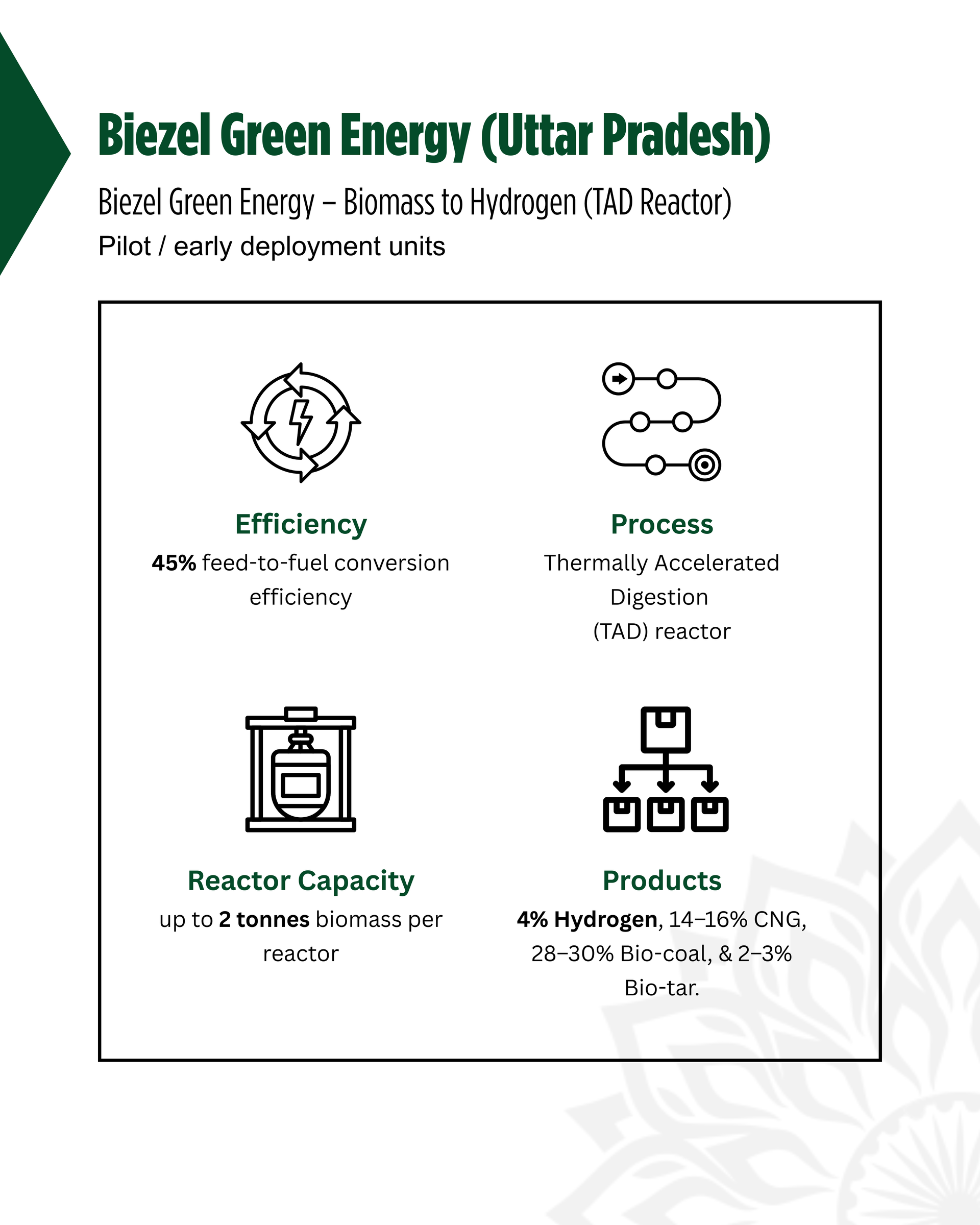

2. Biezel Green Energy, Mirzapur (Uttar Pradesh)

Biezel’s approach is explicitly decentralised. Using a Thermally Accelerated Digestion (TAD) reactor, the system processes up to 2 tonnes of biomass per reactor, achieving about 45% feed-to-fuel conversion efficiency.

Rather than producing pure hydrogen alone, the process yields a mixed energy slate: approximately 4% hydrogen, 14–16% CNG, 28–30% bio-coal, and small quantities of bio-tar. This multi-product model is critical for rural viability, as it creates diversified revenue streams while reducing open-field burning of residues.

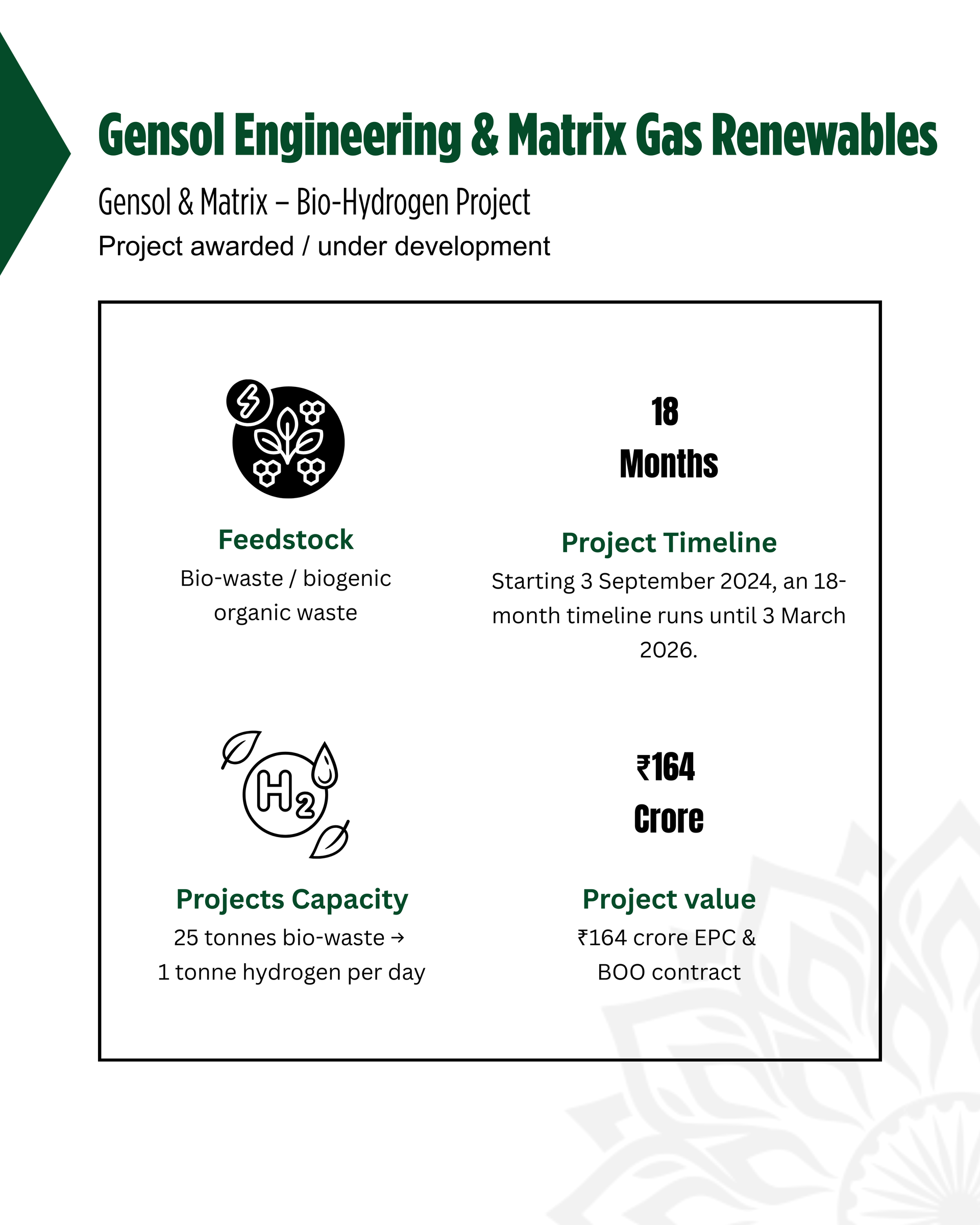

3. Gensol Engineering & Matrix Gas Renewables

This project, awarded in September 2024 with an 18-month execution window, is one of the most commercially structured efforts to date. Designed around 25 tonnes of biogenic waste per day to produce roughly 1 tonne of hydrogen, it operates under a ₹164-crore EPC and BOO (Build–Own–Operate) framework.

This is not a laboratory experiment but an industrial deployment attempt that will test feedstock logistics, continuous operations, and long-term economics of bio-hydrogen.

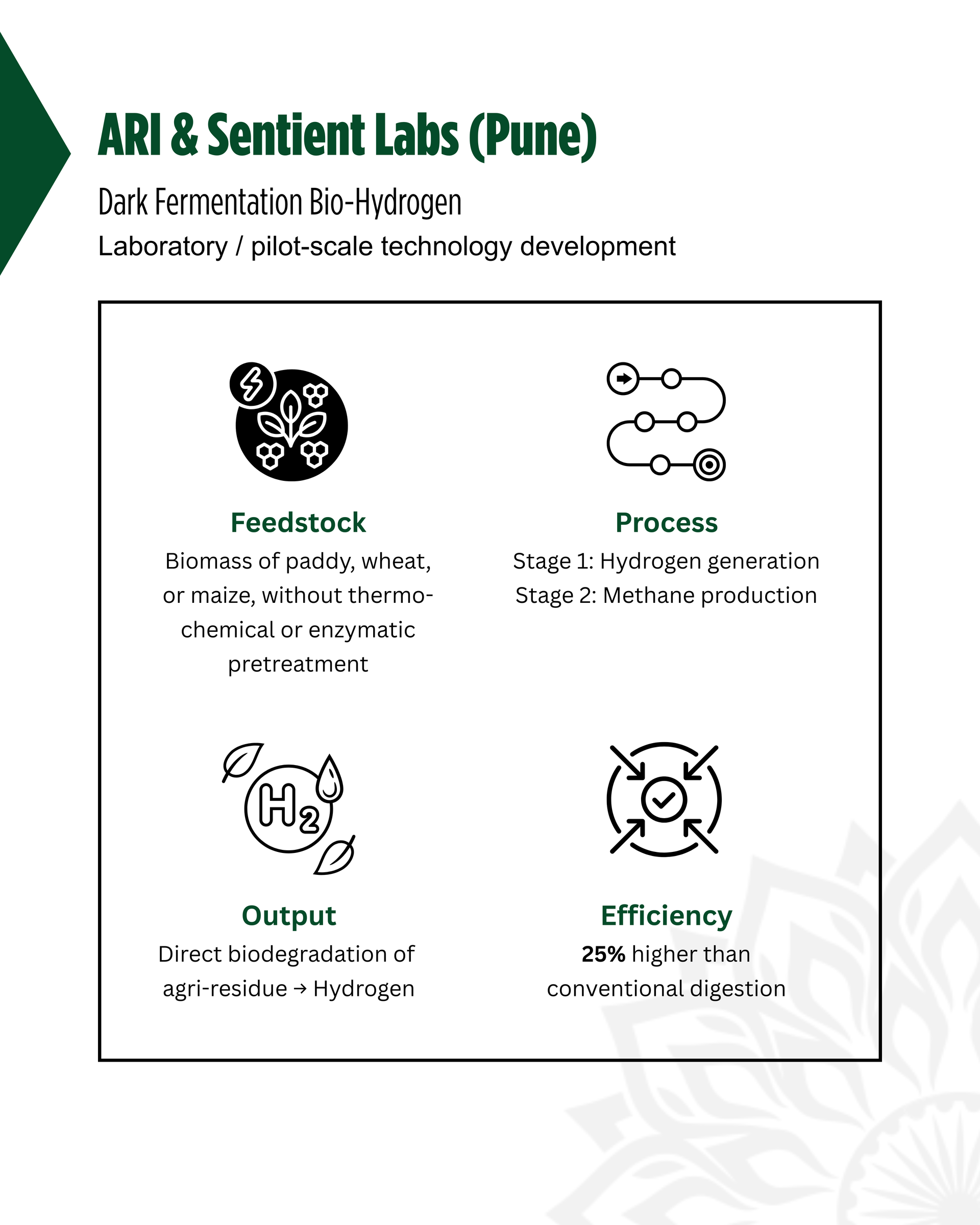

4. Agharkar Research Institute & Sentient Labs, Pune

Here the focus shifts from thermochemical routes to dark fermentation. Using untreated residues from paddy, wheat, or maize, without energy-intensive pre-processing, the system first generates hydrogen and subsequently produces methane in a two-stage process.

Early results indicate about 25% higher efficiency than conventional digestion, suggesting that biological pathways could complement gasification in specific agro-climatic contexts.

Why Policy Support Is Pivotal

These pilots are moving forward largely because of targeted public support. Agencies such as BIRAC and ANERT have played a catalytic role in de-risking early-stage innovation, enabling projects to transition from laboratory prototypes to field deployment.

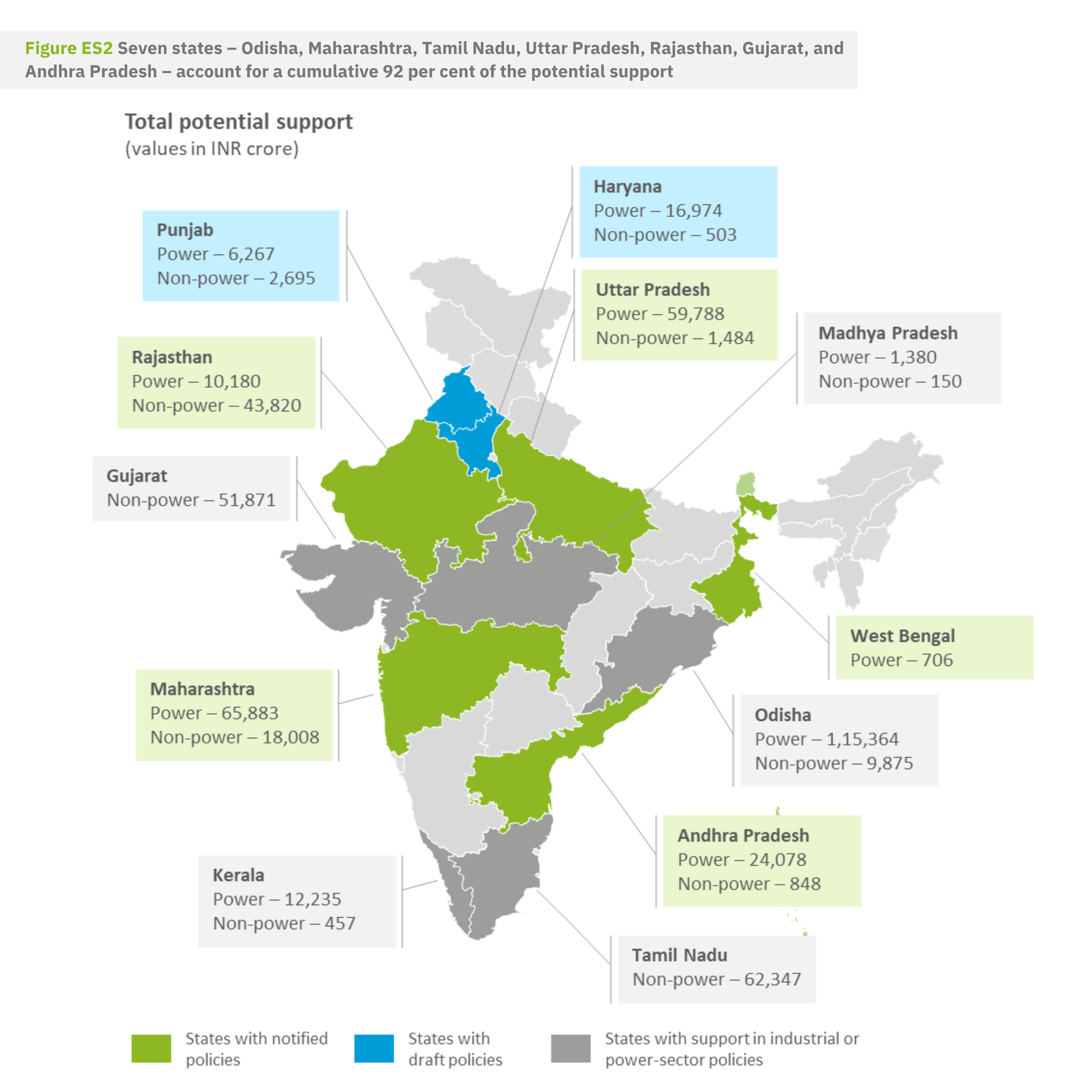

At the state level, Punjab’s Green Hydrogen Policy is particularly significant. Punjab is a residue-rich state where crop burning has long been a public health crisis. By creating incentives for clean hydrogen production, feedstock aggregation, and off-take markets, the policy aligns air-quality goals with industrial decarbonisation, something few jurisdictions have managed to do coherently.

What is still missing at the national level, however, is a clear classification framework for “biogenic hydrogen” within India’s emerging certification architecture. Defining standards for lifecycle emissions, feedstock sustainability, and co-product accounting will determine whether this pathway scales or remains niche.

The Strategic Case for Biomass Hydrogen

India’s hydrogen strategy must rest on three pillars:

- Electrolysis for large-scale green industry and exports.

- Biomass pathways for waste management, rural energy, and distributed production.

- Blended systems where bio-hydrogen complements renewable hydrogen in local clusters.

Biomass-to-hydrogen will not replace electrolysis. It will diversify it, making the transition more resilient, more inclusive, and more politically feasible. The opportunity is not merely technical; it is socio-economic. Every tonne of residue converted into hydrogen is a tonne not burned in fields, not decomposing into methane, and not burdening rural communities with pollution.

If India aligns innovation funding, state policies, and national standards, biomass hydrogen can evolve from scattered pilots into a durable pillar of the country’s clean energy future.