January 14, 2026

Building an India–Europe Green Hydrogen Corridor AM Green, an anchor member of GH2 India, has signed a long-term offtake agreement with Germany-based energy company Uniper for the supply of up to 500,000 tonnes per annum of renewable ammonia from India. Among the largest green ammonia offtake arrangements announced to date, the agreement marks a significant step in positioning India as a reliable global supplier of green hydrogen derivatives. The partnership strengthens the emergence of an India–Europe green hydrogen corridor, with renewable ammonia expected to play a critical role in decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors such as power generation, chemicals, and heavy industry. First deliveries under the agreement are expected to commence around 2028, subject to project development and commissioning timelines.

By Yashaswini Basu Legal and Policy Advisor

•

July 18, 2025

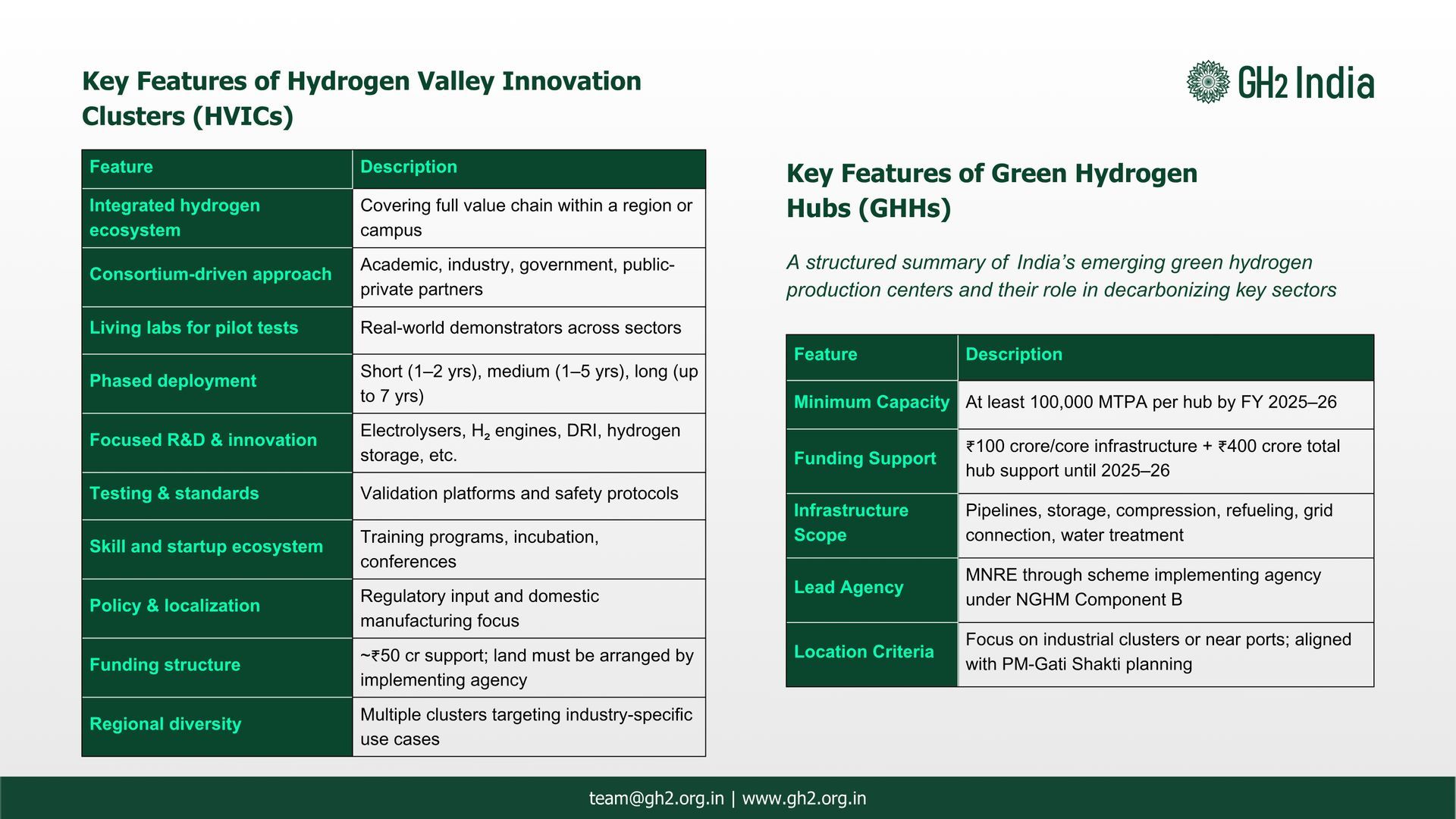

The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (Hydrogen Division) (MNRE) last month released a set of guidelines on setting up Green Hydrogen Hubs (GHH) and Hydrogen Valley Innovation Centres (HVIC) across the country, pursuant to the goals enlisted in the National Green Hydrogen Mission to boost business innovation around the green hydrogen The Guidelines lay down a detailed roadmap for the development of the GHHs and the HVICs including objectives, implementation methodologies and authorities as well as expenditure schemes. The Guidelines envision HVICs as ‘test beds’ or ‘living labs’ for facilitating innovations in green hydrogen across diverse fields, facilitating experiential learning and deriving insights from existing hydrogen pilot projects. They will also foreground business models, map out techno-economic viability of hydrogen projects and foster strategic partnerships between hydrogen producers and off-takers. Based on the outcome of the HVIC, regulatory framework and policies shall be framed subsequently to further accelerate the development of hydrogen-based projects and realise the goals under the NGHM. HVICs have also been tasked with developing the capacity to localise and integrate the entire green hydrogen value chain, generate demand, and secure uptake for end-use of the hydrogen applications. HVICs must also arrange for the acquisition of land for the project. The funds endowed for this will not cover land acquisition and setting up costs. The guidelines further contemplate hydrogen hubs as an ecosystem of hydrogen producers, end-users, and adequate supporting infrastructure including storage, transportation, and processing facilities based around a particular geographical region. They may be located either close to ports or inland. Areas with clusters of refineries, fertilisers and other end-use industries also have been identified as preferred locations for hydrogen hubs. The guidelines have set a target production capacity of 100000 Metric Tonnes Per Annum of green hydrogen per hub. All key resources of the hydrogen hubs, including infrastructure and project development, will be mapped under the PM Gati Shakti portal. MNRE has further outlined the details of the implementation of these guidelines in its Annexure. The authority to oversee the implementation of the HVIC will be a Scheme Implementing Agency (SIA) of the Department of Science and Technology while a SIA nominated by MNRE will be responsible for the execution of the GHH. While the guidelines provide an impetus for innovation driven developments in India’s green hydrogen economy, a few causes of uncertainty have also arisen in the recent past. The Solar Energy Corporation’s (SECI) announced the cancellation of the tender for setting up green hydrogen hubs on July 4, 2025, and stated that all the tender management fees or document fees submitted thus far will be refunded. Bidders have been advised to email the concerned persons at SECI with the required documents seeking the refund before July 20, 2025. While no official reason has been released by the government on this matter yet, this has raised questions about the future trajectory of India’s green hydrogen goals as we draw near 2030.

By Yashaswini Basu Legal and Policy Advisor

•

July 4, 2025

Last week the Hon’ble Union Minister of Ports, Shipping and Waterways, Shri Sarbananda Sonowal unveiled the Sagarmala Finance Corporation Limited (SMFCL), the first of its kind Non-Banking Financial Company (NBFC) exclusively for the maritime sector. In its previous avatar as the Sagarmala Development Company Limited, SMFCL was the key implementing entity for the Sagarmala Programme, encompassing project development and formulation to fund raising and Coastal Economic Zones master plan, among others. This remodelling comes as a response to the long-standing demand of the maritime industry for a sector specific financing institution and is in alignment with India’s goal to emerge as a global maritime leader under the Amrit Kaal Vision 2027. On account of the maritime industry being a capital-intensive sector which is slow to yield returns with regulatory strictures, investment prospects are often limited. This risky and yet niche sector struggled to procure private lending from banks and private investors and thus the need for a unified financial institution dedicated just to the marine industry was reinforced. On June 19, 2025 SMFCL was formally registered as an NFBC with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and is categorised as a Mini Ratna, Category I, Central Public Sector Enterprise. With the Tier 1 capital estimated at Rs 680 crore, SMFCL has the capacity to offer bigger loans with consortium partners, valuing up to Rs 3400 crores. With the objective of bridging the financial gaps in the maritime industry, SFMCL will provide financial support towards empowering ports, MSMEs, startups, and maritime educational institutions. As a dedicated financing body, SFMCL is poised to usher in significant transformation in the maritime sector and accelerate industry wide growth, sustainability and innovation. It will also extend to strategic sectors like shipbuilding, renewable energy, cruise tourism, and maritime education. Overall, by enabling access to a focused financial opportunity, SFMCL will leverage efficiencies and inclusive development in the maritime sector, thus propelling India towards global maritime leadership. Built akin to other successful development financial institutions in India like the Indian Railway Finance Corporation for the railways, SMFCL comes with an expanded funding horizon and several other essential services. These include blended finance instruments like equity, subordinated debts, debts etc. It will also support Private Public Partnerships (PPPs) in financing logistics corridor, coastal infrastructure among others. SMFCL’s founding is a critical step towards steering India’s maritime sector at par with the global standards. The European Commission launched the Ship Financing Portal in July 2024, serving as a centralized repository of financing products for the EU-based maritime sector. This is complemented by European Investment Bank’s (EIB) co-financing maritime sector project. Similarly, in Japan, the SMBC Group operates a global maritime finance division, leveraging its strong balance sheet and institutional dedication to the shipping industry to provide long-term support. SMFCL is not only likely to help the maritime industry overcome the financial bottlenecks but also will greatly boost the green transition in the maritime industry, as envisioned in India ’Gateway to Green roadmap. Streamlined funding will help amplify green hydrogen capacity at ports and bunkering stations, and enable shore power infrastructure, etc. This brings in the much-needed transformation to the erstwhile fragmented investment space for the maritime industry and enables SMFCL to cater to the unique capital requirements of the maritime and shipping sector.

By Parth Sharma, Programme Associate, GH2 India

•

July 4, 2025

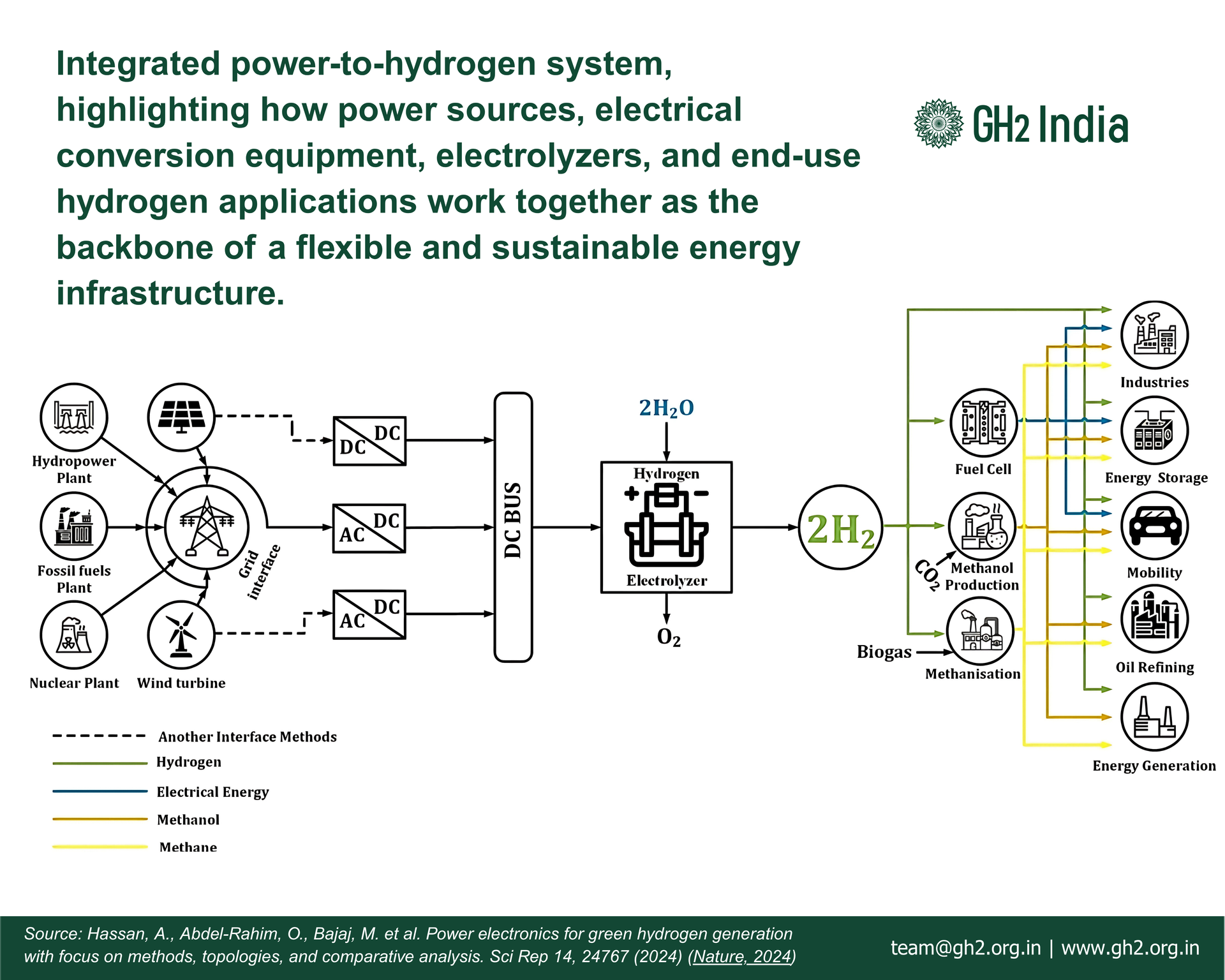

India has committed to producing 5 million tonnes of green hydrogen per year by 2030, supported by approximately 125 GW of new renewable generation capacity (CEEW, 2024). Yet behind this high-profile ambition lies a less discussed but arguably more decisive factor: the vast electrical infrastructure required to turn fluctuating renewable electricity into the stable, precisely controlled DC power that electrolyzers need. This is the real machinery that converts photons and winds into hydrogen molecules, and it is expensive, complex, and often invisible in public debates (Iris CNR, 2024). Today, India’s green hydrogen costs hover between ₹397–₹560 per kilogram ($4.6–$6.7/kg) , which is two to three times the cost of grey hydrogen produced from natural gas. Nearly 95% of this cost is tied to capital investment and financing , and within that, 30–50% comes from electrical systems alone. For a single 100 MW PEM electrolyzer project , that means ₹1,000–1,200 crore ($120–145 million) just in transformers, rectifiers, converters, switchgear, sensors, and control systems (CEEW, 2024). In other words, the electrons are not only expensive because renewable power isn’t free, but they are also expensive because they must be processed, stabilized, and delivered with extraordinary precision. Hydrogen electrolysis is an energy-intensive process, requiring 50–55 kWh/kg H₂ including losses (Iris CNR, 2024). Of this, power conversion losses typically account for 1–2 kWh/kg, equivalent to 2–4% of total energy input. Technical benchmarks help illustrate what’s at stake: Thyristor-based SCR rectifiers achieve >98.5–99% efficiency at full load but suffer poor power factor (<0.7) and up to 30% total harmonic distortion (THD) if not mitigated with filters. Active front-end IGBT converters deliver 96–97% efficiency but maintain near-unity power factor and <5% THD (ResearchGate, 2024). A 100 MW electrolyzer operating 7,000 hours/year will consume 700 GWh/year of AC input. If conversion losses are reduced from 4% to 2%, the plant saves 14 GWh/year, translating to ₹70–85 crore/year at industrial tariff rates (~₹5–6/unit). Ripple reduction is equally critical: PEM stacks degrade faster under >5% DC ripple. High-frequency interleaved DC-DC converters can cut ripple below 1%, extending stack life from ~60,000 to ~80,000 hours (Iris CNR, 2024).

By Kamya kalra, Policy Associate, GH2 India

•

June 27, 2025

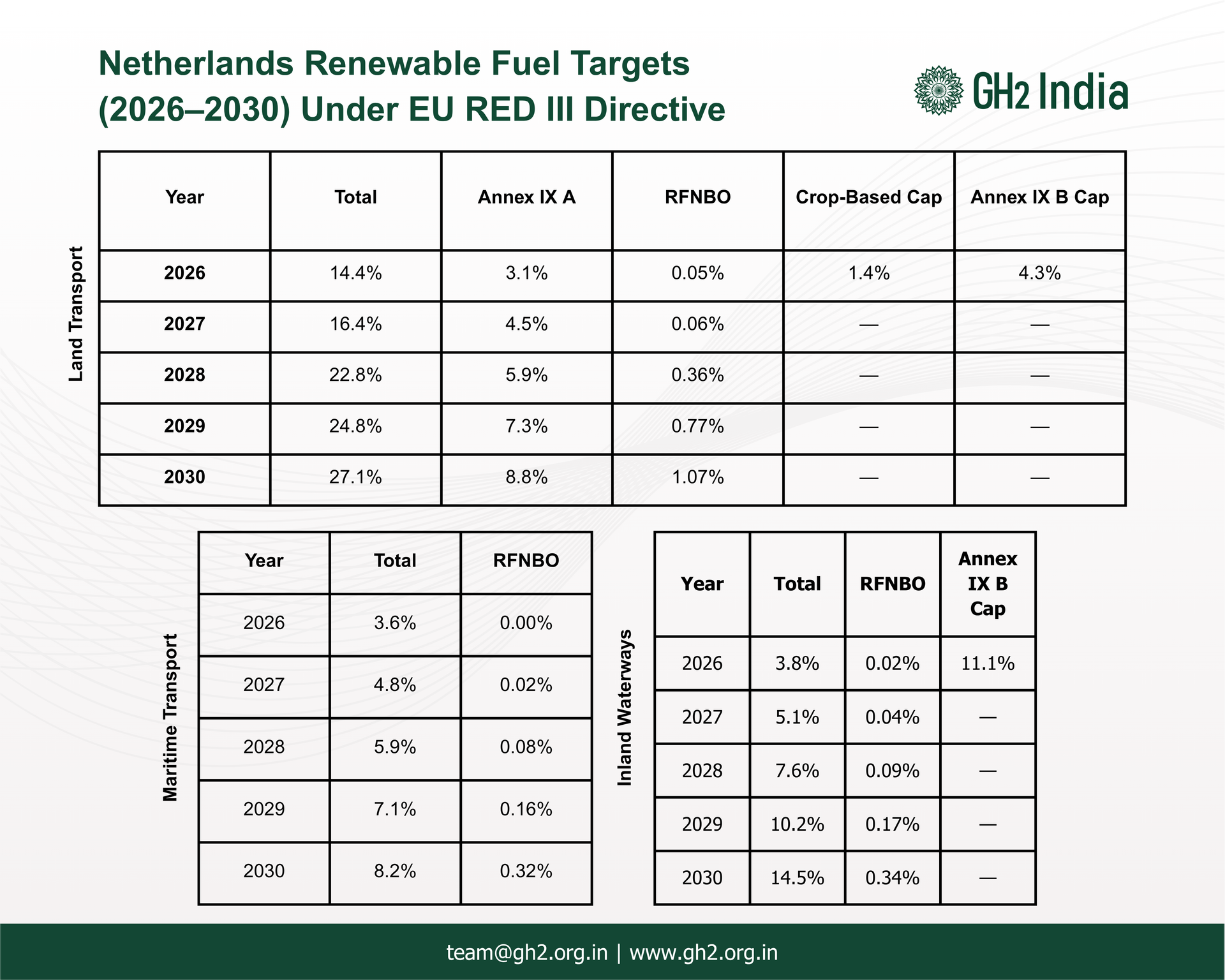

On 24 June 2025, the Dutch Ministry for Infrastructure and Water Management released the draft “Implementation of RED III” regulation to transpose the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive III. This draft outlines obligations for renewable energy uptake in the transport sectors, land, inland shipping, and maritime, while notably excluding aviation. This is aimed at eschewing instances of double counting of renewable energy contributions from raw materials enlisted under Annex IX of RED II. It follows an EU Commission request to comply by 25 May 2025 on setting designated acceleration zones and further aligning with EU timelines (implementation beginning in 2026) The proposal mandates a phased increase in the share of renewable energy in transport fuels, from 14.4% in 2026 to 27.1% by 2030, using a GHG-based accounting system referred to as Energy Reduction Units. Obligated suppliers, with overall consumption more than 500,000/year, will be required to surrender EREs annually. While EREs from the land transport sector can be used to meet shipping obligations, the reverse will not be permitted. The draft sets a cap on crop-based biofuels at 1.2% of total energy for the land sector, consistent through 2030. For biofuels based on Annexe IX Part B feedstocks such as used cooking oil and animal fats, the land sector is capped at 4.29%, inland shipping at 11.07%, and the maritime sector is excluded altogether. The Dutch government has also opted to decouple the EU-wide 5.5% advanced biofuels and 1% RFNBO sub-targets, allowing them to be met separately. Renewable hydrogen used in refineries will count towards a separate RAREs (Refinery Assigned Reduction Effort) obligation, offering another pathway for compliance. A hydrogen “correction factor”, which would reduce the creditable value of hydrogen as a fuel, will not be applied in the near term, and may only be introduced after 2030, reflecting the government’s commitment to support the direct use of hydrogen. To maintain fuel quality standards, the Netherlands will retain its current B7 biodiesel blend limit, despite EU provisions allowing up to B10, citing concerns about compatibility with older diesel vehicles. The existing Dutch renewable fuel credit system, known as HBEs, will be converted into EREs effective from 1 April 2026. Credit banking will be allowed, with a limit of 10% for obligated parties and 4% for registered entities. The phased renewable energy targets and crediting mechanisms provide regulatory clarity for investors and market participants. For India, the clear caps on conventional feedstocks, combined with rising RFNBO and advanced biofuel targets, signal a growing demand for renewable hydrogen and synthetic fuels within the EU. This may make it exigent to re-adjust our focus from the existing cooking oil and animal fat markets towards investments in advanced biofuels. The delay in applying a correction factor for hydrogen further strengthens the case for direct hydrogen use, particularly in refining applications. These provisions align well with India’s strengths in low-cost renewable hydrogen production and create a scope for technology transfer, supply partnerships, and strategic advisory roles targeting Europe’s evolving clean fuels market. This draft regulation provides clarity on the Netherlands’ implementation approach and introduces a structured compliance mechanism that emphasizes the role of advanced biofuels and renewable hydrogen in transport decarbonization. For emerging producers and exporters of renewable hydrogen and e-fuels, including Indian developers, this framework offers regulatory signals worth monitoring closely.

By Kamya kalra, Policy Associate, GH2 India

•

June 25, 2025

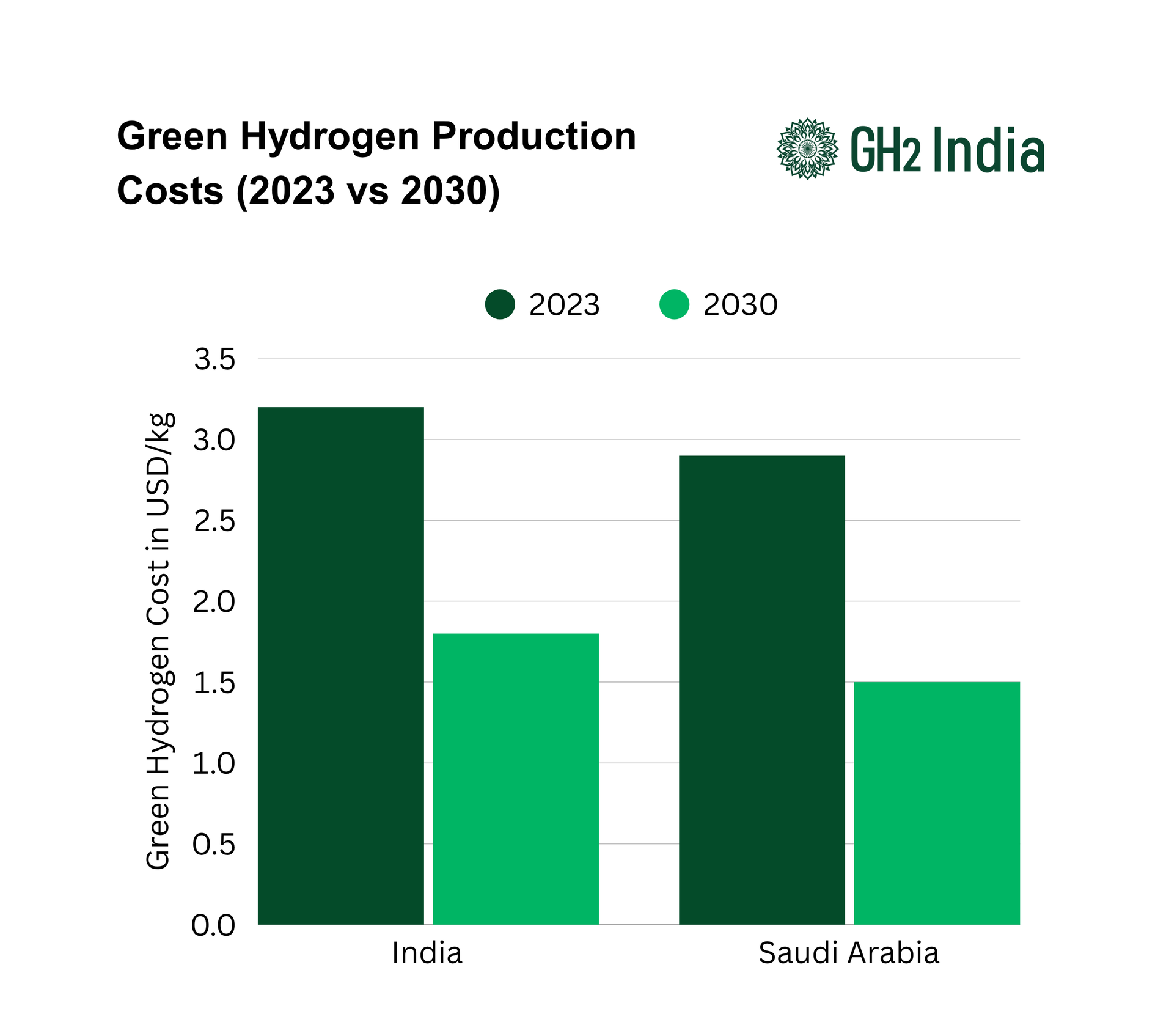

Saudi Arabia is investing heavily to become a global hydrogen export hub. Under its National Hydrogen Strategy, launched in 2021 as part of Vision 2030, the Kingdom aims to become one of the top three global hydrogen producers by the next five years. Its $8.4 billion NEOM plant, a 4 GW solar wind electrolysis, is designed to produce 600 tons of green hydrogen per day (roughly 1.2 million tonnes of ammonia per year), with its first output around 2026. India’s National Green Hydrogen Mission (launched 2023) sets similarly grand goals of producing 5 million tonnes per year by 2030. Meeting this requires the order of 125 GW of new renewable capacity. The government has committed large subsidies, roughly ₹8 lakh crore, but policy aims to reduce them toward $1.5/kg by 2030 (Raizada, 2025; Sawhney, 2024). However, India faces resource and infrastructure challenges. Land, water and grid limitations could bottleneck expansion (Gili & De Blasio, 2024). To address these constraints and enhance supply security, India is actively building hydrogen partnerships, with Saudi Arabia emerging as a strategic collaborator. For example, the proposed India, Middle East, Europe corridor would pipe H₂ via UAE, Saudi, Jordan, etc., linking Indian supply to European markets. An April 2025 summit between Prime Minister Modi and Crown Prince MBS explicitly committed to joint hydrogen R&D and trade facilitation (SolarQuarter, 2025). This bilateral hydrogen cooperation is grounded in shared goals of scaling clean energy, developing resilient infrastructure, and enhancing grid and transport connectivity. Infrastructure and cost comparisons underscore these dynamics. Saudi Arabia’s advantage comes from extremely cheap power and capacity factors: analysts project Saudi production costs as among the world’s lowest. By contrast, India’s higher capital costs make domestic green H₂ significantly more expensive. Transport adds cost too, converting and shipping hydrogen can add on the order of $1 or $2/kg (Hydrogen Council 2021), narrowing price gaps. India must therefore build ports, storage and pipeline connections for imports or dramatically expand its grid for in-country H₂, a complex engineering and fiscal task. Saudi’s scale hence puts downward pressure on global H₂ prices, which Indian policymakers must account for. Strategically, the relationship is not defined by the NEOM project alone. It includes broader policy alignment, clean-tech collaboration, and skilled labour partnerships . It is true global buyers (e.g. in Japan/Korea) have bought blue hydrogen at $1.7/kg, undercutting green hydrogen (Singh, 2024). India’s exporters worry without guarantees they may lose out. However, cooperation, not competition, defines the bilateral narrative. India and Saudi both emphasize hydrogen storage/transport collaboration and circular carbon approaches. Observers argue that leveraging Saudi supplies (through offtake agreements or joint ventures) could improve India’s energy security and accelerate its own transition (Raizada, 2025). With adequate safeguards (diversifying import sources, ensuring domestic build-out), Saudi hydrogen can act as a catalyst, pushing India to scale up faster while supplying low-carbon energy, rather than as an insurmountable competitor (Gili & De Blasio, 2024; Raizada, 2025). Saudi Arabia’s hydrogen export push, embedded in its national hydrogen roadmap, is not just a competitive force but a critical input to India’s hydrogen strategy. The Kingdom’s scale clearly adds competitive pressure, but India is framing the relationship as partnership, not rivalry. By securing strategic deals (e.g. the IMEC pipeline concept) and balancing imports with domestic capacity expansion, India aims to turn Saudi hydrogen into an opportunity. In policy terms, Saudi Arabia’s plans motivate India to accelerate its National Hydrogen Mission but do so in a way that leverages mutual interests in energy security and clean tech collaboration (Sawhney, 2024; Singh, 2024). The prevailing view is that, with proper planning, Saudi hydrogen will spur India’s transition rather than derail it.

By Yashaswini Basu Legal and Policy Advisor

•

June 19, 2025

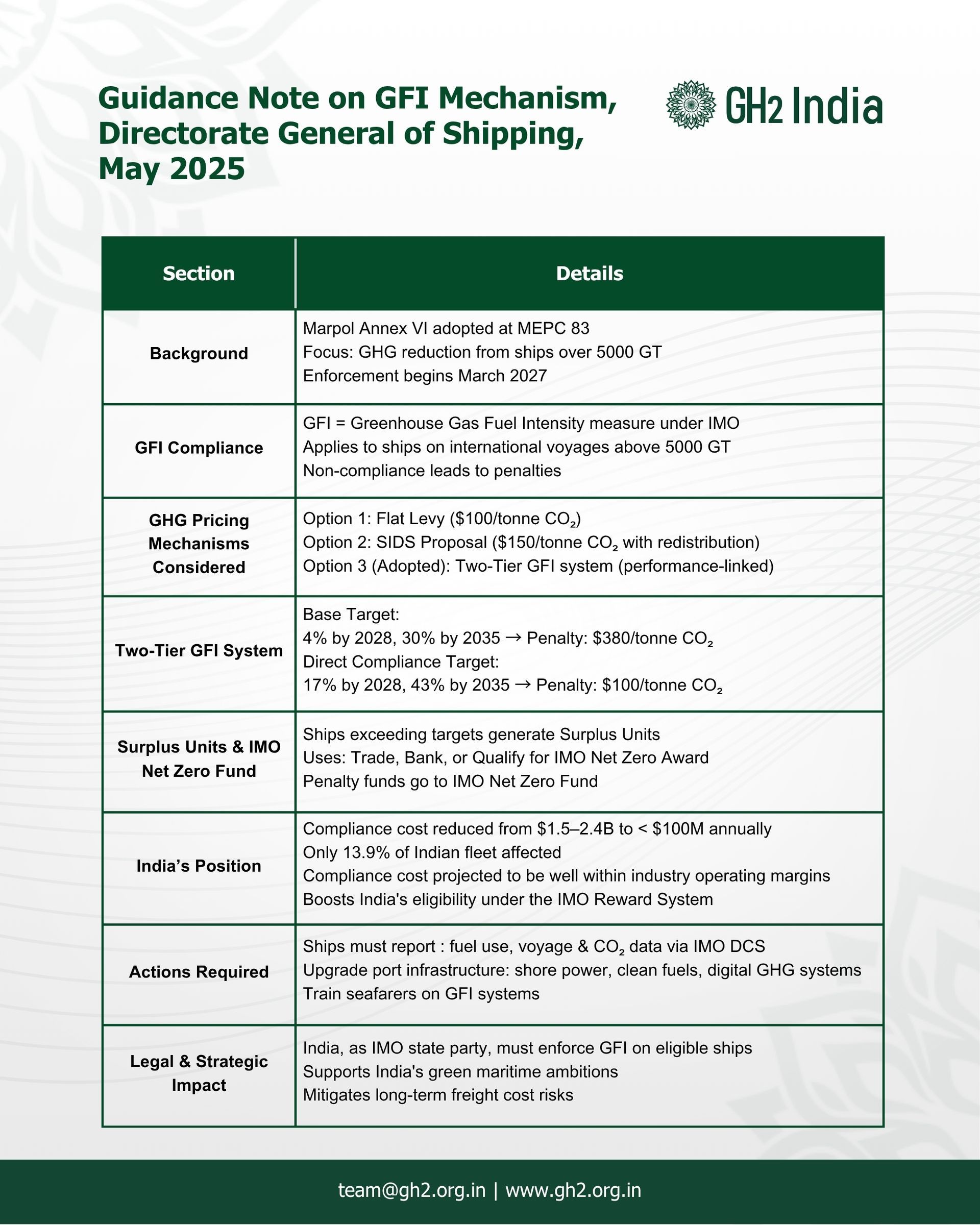

Earlier this May, the Directorate General of Shipping released a guidance note to carve out a roadmap for India to comply with Marpol Annex VI adopted this year at MEPC 83. This note explains the key provisions of Marpol Annex VI and aims to build preparedness among the Indian Shipping industry with respect to the upcoming regulations under IMO’s framework. GFI Compliance Adopted at MEPC 83, the Greenhouse Gas Fuel Intensity (GFI) measure is a mechanism to progressively reduce greenhouse gas emissions from ships above 5000 GT. Marpol Annex VI has set specific GFI limits which ships on international voyages must follow or face penalties. The GFI is set to come into force in March 2027. Having considered the three different methods under the GHG pricing mechanism, including a flat levy where ships will be uniformly penalised at $100 per tonne of CO2 emitted; a higher penalty of $150 per tonne of CO2 emitted but the penalty redistributed among different sectors for climate vulnerable countries through the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) proposal; and, the Two-tier GFI mechanism which is a performance linked system penalising ships with high GFIs while rewarding those with GFI below the target levels, the later was adopted through a majority vote at the MEPC 83. The two tier GFI mechanism entails, eligible ships to abide by two levels of targets; a) A Base Target which aims for decarbonisation at 4% by 2028 and 30% by 2035 and b) The Direct Compliance Target aiming at decarbonisation at 17% by 2028 and 43% by 2035. This mechanism levies penalties in the form of ‘remedial units’ for failure to meet the targets. For failing to meet the base target, a higher remedial unit purchase worth $380 per tonne of CO2 is set out while a failure to meet the direct compliance target, ships must purchase remedial units worth $100 per tonne of CO2. Ships which surpass these targets can also generate ‘Surplus Units’, which can be used to trade with other ships in lieu of other benefits; or banked for future use; or even used to qualify for the IMO Net Zero Award. The GFI mechanism also lays down a plan for redistribution of the funds generated through the penalties. These will be held under the IMO Net Zero Fund which can be encashed for financial incentives to well performing ships, assist developing countries in their climate initiatives etc. India’s Position The Note elaborates on India’s position on the GFI mechanism : The flexible pricing mechanism under GFI benefitted India by firstly, reducing the cost impact from $1.5- $2.4 billion annually to under $100 million, compared to a flat levy structure. It incentivises adoption of clean technologies while being well aligned with India’s climate transition strategies. The GFI mechanism however does not impact Indian fleet much. Only 13.9% of Indian ships come under the purview of the GFI mechanism. The GFI mechanism is expected to increase India’s compliance cost by $ 87–100 million annually by 2030 which is well within the industry operating margins. This also promotes synchronisation of India’s projected production capacity of green ammonia and methanol by 2030 with the eligibility criteria of the IMO GFI reward system. This will also boost India’s export potential and investment in clean energy. Action Needed Ships which are eligible under the IMO framework must annually report fuel consumption, voyage data, and carbon intensity metrics through the standardized IMO Data Collection Systems. Aligning ports infrastructure through improved shore power, digital GHG inspection systems, and clean fuel availability to the GFI system will amplify Indian ports’ position as a green bunkering hub. Indian seafarers must have their capacities and awareness built on operational knowledge of GFI reporting, fuel lifecycle characteristics, remedial unit tracking, and voyage planning for emission optimization Indian ships involved in international trade must factor GHG compliance in order to reduce long-term freight inflation risks. While India retains the sovereign right over the enforcement of Marpol Annex VI, as a state party of IMO, it will be under the legal obligation to ensure the eligible ships remain compliant with GFI mechanisms. This will also be advantageous for India from a fiscal standpoint and reinforce India’s influence in shaping global governance of the green shipping landscape.

By Yashaswini Basu Legal and Policy Advisor

•

June 10, 2025

India and Japan have had a long standing kinship across the realms of business, politics and, art and culture. In the recent times, the maritime sector has emerged has one of the key areas of collaboration between them. From the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) vision to the latest high level bilateral meetings between dignitaries from the two countries, India and Japan have fostered a robust relationship in facilitating growth and innovation in the maritime industry. Some of the key milestones in the Indo-Japan maritime strategy are : Free and Open Indo-Pacific Vision, 2020 : Both countries share the vision to nurture the pillars of FOIP in building economic capabilities; improving maritime security and connectivity; promoting sustainable development and collective security. QUAD Framework : As members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD), India and Japan have mutually committed to strengthening maritime resilience and security through collaborative naval drills, interoperable disaster response mechanisms etc. India- Japan Clean Energy Partnership , 2022 : A strategic initiative launched to jointly promote both countries' decarbonisation efforts through pilot projects as well as research and development projects in green hydrogen and green ammonia-based fuels, carbon recycling technologies etc. The latest highlight in the chain of Indo-Japan maritime ties, is the High-Level Bilateral Meeting held last week at Oslo, Norway between Shri Sarbananda Sonowal, Union Minister of Ports, Shipping and Waterways, India and Mr. Terada Yoshimichi, Japan’s Vice Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport & Tourism. The meeting re-affirmed both countries' commitment to mutually boost investment and development of sustainable fuels, digitisation of ports, upskilling and employment opportunities for seafarers among other discussions. Smart Islands : Appreciating Japan's expertise in developing island territories, India invited Japan's cooperation in the quest to transform Lakshadweep and Andaman and Nicobar islands into Smart Islands. Clean Energy Hubs : The Ministers of both the countries discussed greenfield investments like the pilot project, Imabari Shipyard in Andhra Pradesh and the prospects for development of more clean energy hubs jointly between leading Japanese shipbuilding companies and Indian yards. Other infrastructural and economic collaborations : Both countries assessed potential MoUs between relevant Japanese stakeholders and Cochin Shipyard Limited and other Indian maritime educational institutes and public agencies. Further, the feasibility of integrating India's 154000 trained seafarers in Japan's maritime missions was deliberated upon. Finally, Shri Sonowal invited Japan to partner in the development of the National Maritime Heritage Museum in Lothal, Gujarat. India has set a target of five trillion yen as investment from Japan by 2027 and the high-level meeting evinced substantial and sustainable progress in the bilateral maritime ties between India and Japan going forward. This meeting comes at an opportune moment in the wake of the World Hydrogen Asia Conference scheduled between July 8th and July 10th, 2025 at Tokyo, Japan. As supporting partners to the conference, GH2 India will be steering insightful discussions and follow ups on securing Asia's sustainable future with hydrogen and low carbon fuels.