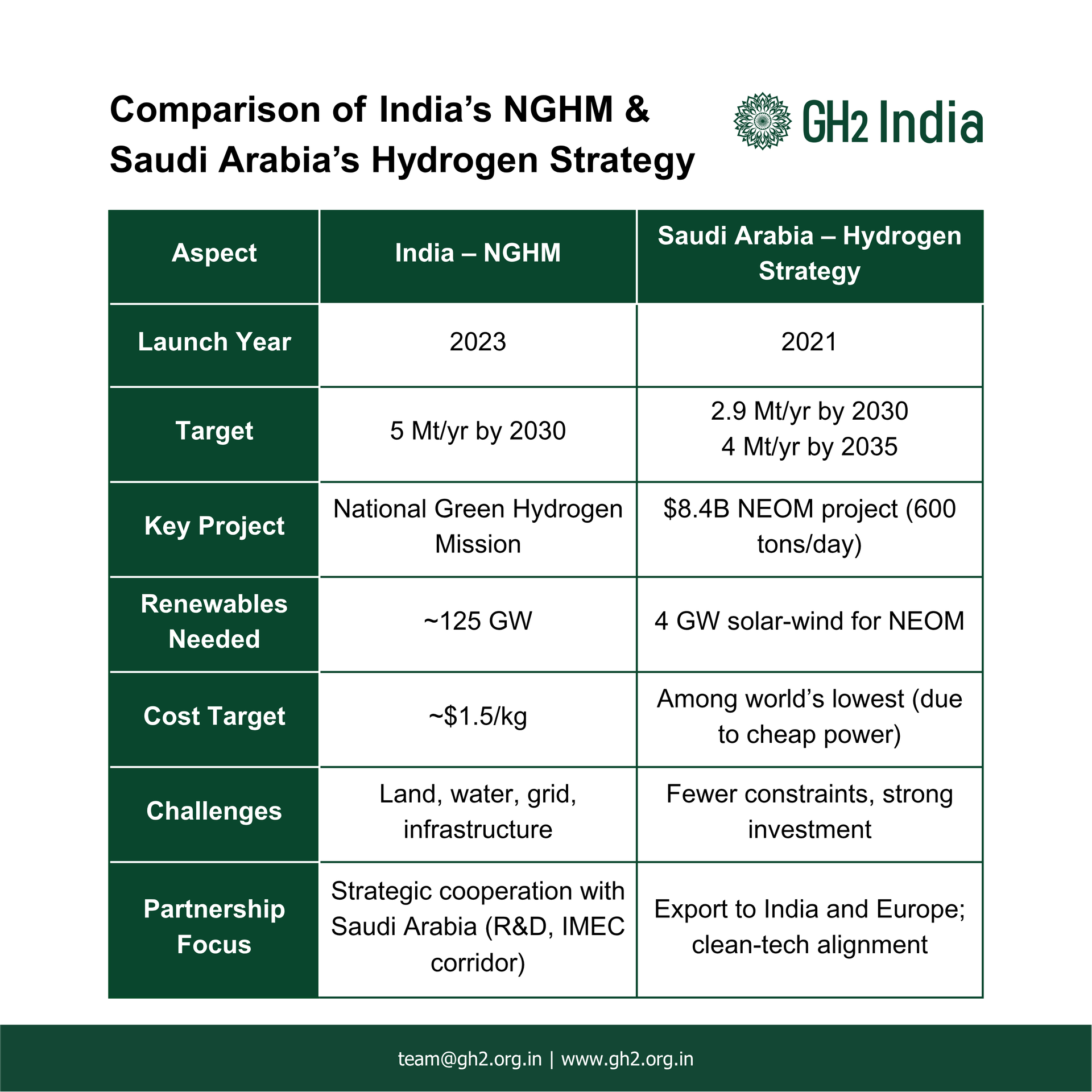

Saudi Arabia is investing heavily to become a global hydrogen export hub. Under its National Hydrogen Strategy, launched in 2021 as part of Vision 2030, the Kingdom aims to become one of the top three global hydrogen producers by the next five years. Its $8.4 billion NEOM plant, a 4 GW solar wind electrolysis, is designed to produce 600 tons of green hydrogen per day (roughly 1.2 million tonnes of ammonia per year), with its first output around 2026.

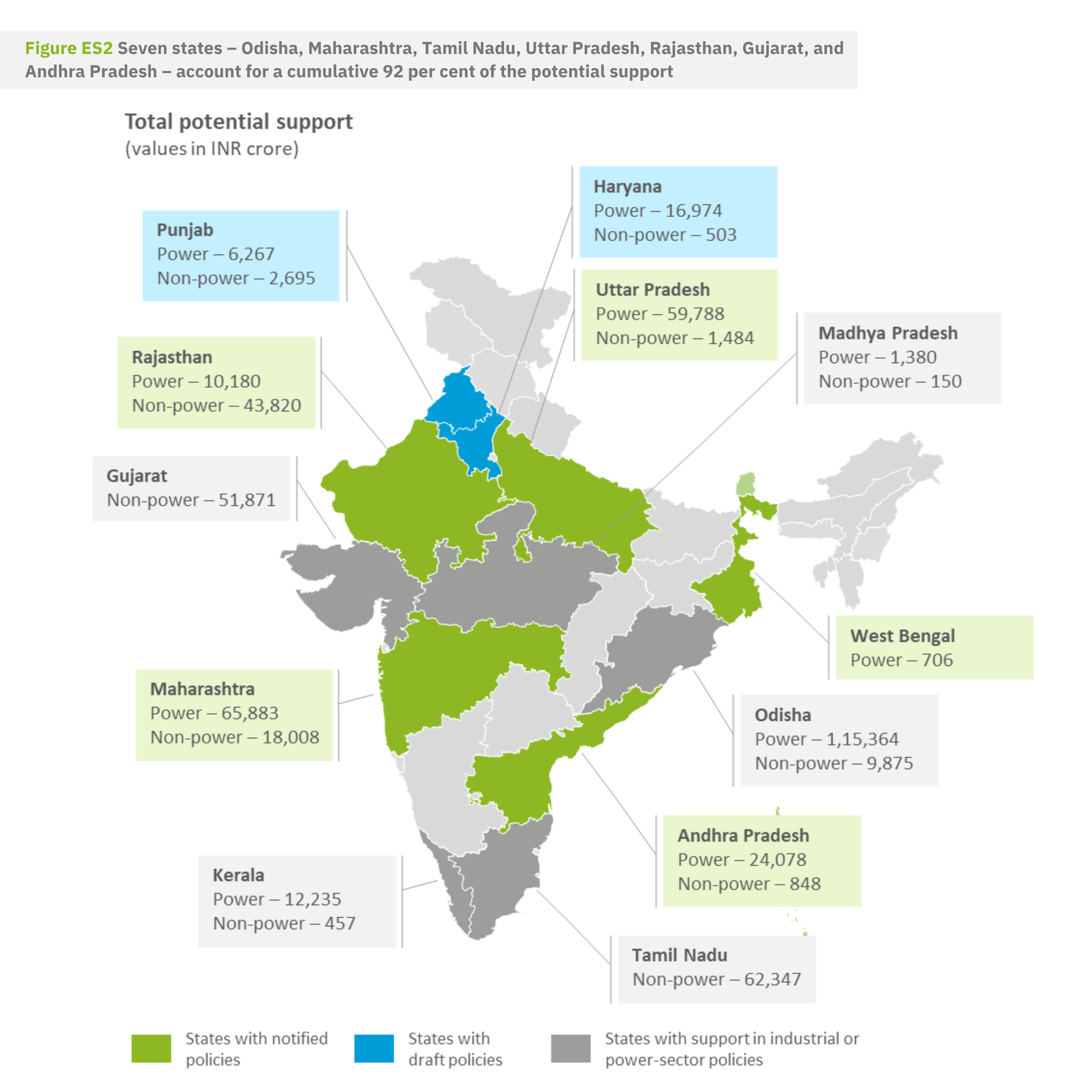

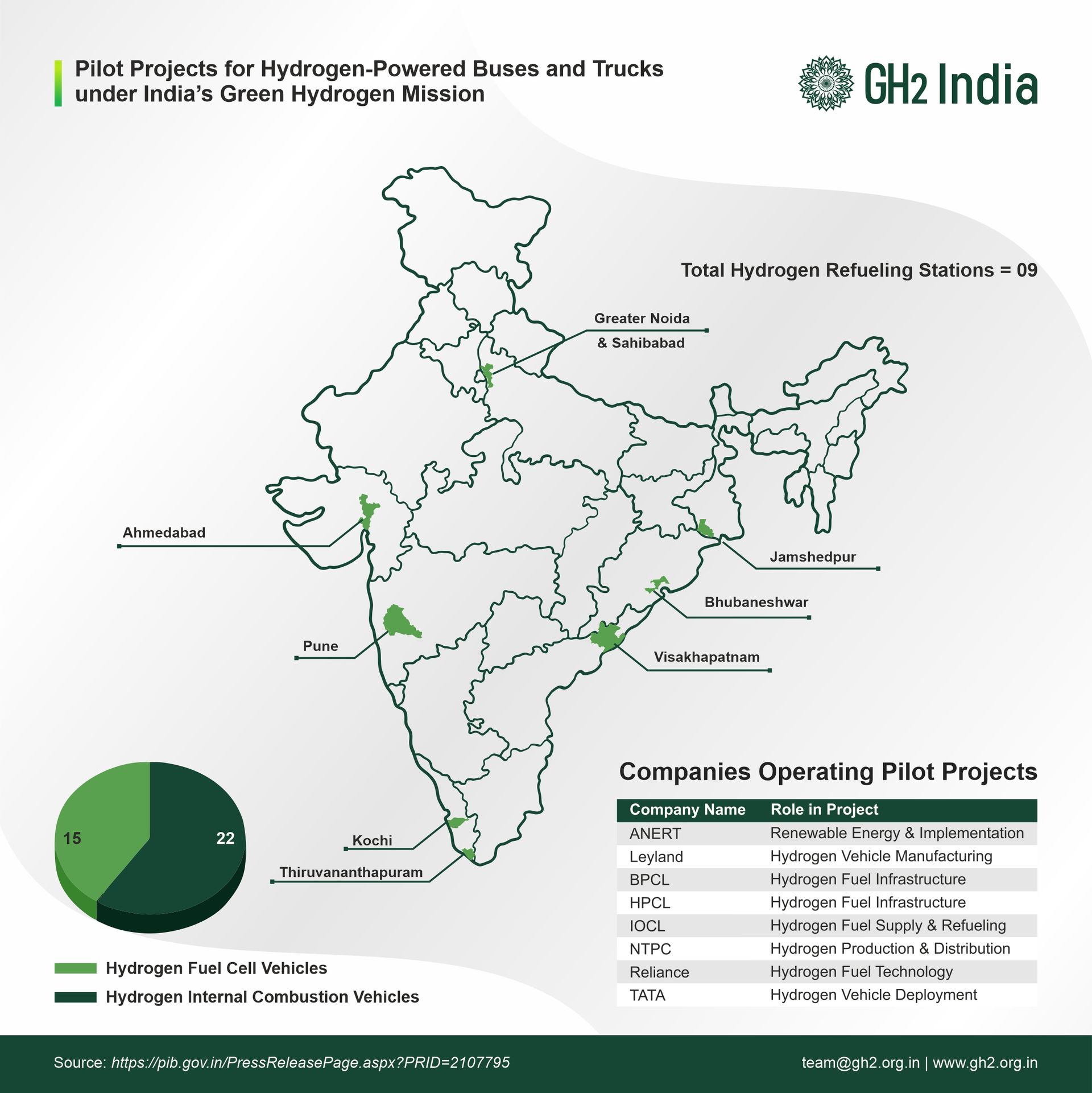

India’s National Green Hydrogen Mission (launched 2023) sets similarly grand goals of producing 5 million tonnes per year by 2030. Meeting this requires the order of 125 GW of new renewable capacity. The government has committed large subsidies, roughly ₹8 lakh crore, but policy aims to reduce them toward $1.5/kg by 2030 (Raizada, 2025; Sawhney, 2024). However, India faces resource and infrastructure challenges. Land, water and grid limitations could bottleneck expansion (Gili & De Blasio, 2024).

To address these constraints and enhance supply security, India is actively building hydrogen partnerships, with Saudi Arabia emerging as a strategic collaborator. For example, the proposed India, Middle East, Europe corridor would pipe H₂ via UAE, Saudi, Jordan, etc., linking Indian supply to European markets. An April 2025 summit between Prime Minister Modi and Crown Prince MBS explicitly committed to joint hydrogen R&D and trade facilitation (SolarQuarter, 2025). This bilateral hydrogen cooperation is grounded in shared goals of scaling clean energy, developing resilient infrastructure, and enhancing grid and transport connectivity.

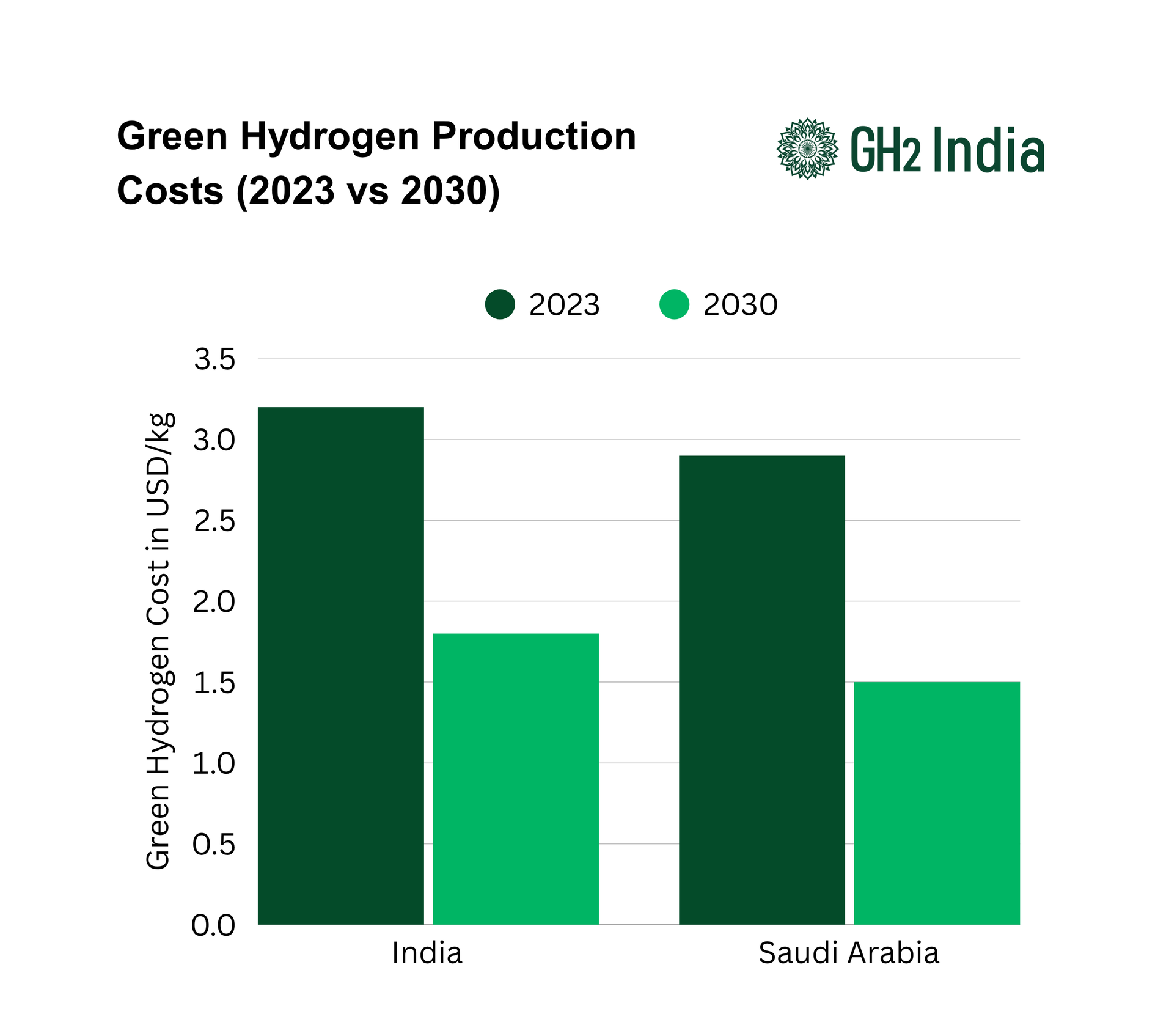

Infrastructure and cost comparisons underscore these dynamics. Saudi Arabia’s advantage comes from extremely cheap power and capacity factors: analysts project Saudi production costs as among the world’s lowest. By contrast, India’s higher capital costs make domestic green H₂ significantly more expensive. Transport adds cost too, converting and shipping hydrogen can add on the order of $1 or $2/kg (Hydrogen Council 2021), narrowing price gaps. India must therefore build ports, storage and pipeline connections for imports or dramatically expand its grid for in-country H₂, a complex engineering and fiscal task. Saudi’s scale hence puts downward pressure on global H₂ prices, which Indian policymakers must account for.

Strategically, the relationship is not defined by the NEOM project alone. It includes broader policy alignment, clean-tech collaboration, and skilled labour partnerships. It is true global buyers (e.g. in Japan/Korea) have bought blue hydrogen at $1.7/kg, undercutting green hydrogen (Singh, 2024). India’s exporters worry without guarantees they may lose out. However, cooperation, not competition, defines the bilateral narrative. India and Saudi both emphasize hydrogen storage/transport collaboration and circular carbon approaches. Observers argue that leveraging Saudi supplies (through offtake agreements or joint ventures) could improve India’s energy security and accelerate its own transition (Raizada, 2025). With adequate safeguards (diversifying import sources, ensuring domestic build-out), Saudi hydrogen can act as a catalyst, pushing India to scale up faster while supplying low-carbon energy, rather than as an insurmountable competitor (Gili & De Blasio, 2024; Raizada, 2025).

Saudi Arabia’s hydrogen export push, embedded in its national hydrogen roadmap, is not just a competitive force but a critical input to India’s hydrogen strategy. The Kingdom’s scale clearly adds competitive pressure, but India is framing the relationship as partnership, not rivalry. By securing strategic deals (e.g. the IMEC pipeline concept) and balancing imports with domestic capacity expansion, India aims to turn Saudi hydrogen into an opportunity. In policy terms, Saudi Arabia’s plans motivate India to accelerate its National Hydrogen Mission but do so in a way that leverages mutual interests in energy security and clean tech collaboration (Sawhney, 2024; Singh, 2024). The prevailing view is that, with proper planning, Saudi hydrogen will spur India’s transition rather than derail it.

References (APA):

Abuljadayel, F. (2022, September 29). Saudi green hydrogen production costs could be lowest in the world: KAPSARC. Arab News.

Council on Energy, Environment and Water. (2024). Augmenting the National Green Hydrogen Mission: Assessing potential policy support in India.

Gili, A., & De Blasio, N. (2024, March 26). India – The New Global Green Hydrogen Powerhouse? Belfer Center, Harvard Kennedy School.

Government of India, Ministry of New & Renewable Energy. (2024). National Green Hydrogen Mission. Press Information Bureau.

Raizada, A. (2025, May 5). India’s Green Hydrogen Strategy in Action: Policy actions, market insights, and global opportunities. IFRI.

Saudi Energy Consulting. (2025, March 12). Saudi Arabia to export 200k tons of green hydrogen to Europe by 2030.

Sawhney, R. (2024, May 1). Decoding India’s Green Hydrogen Potential. Observer Research Foundation (ORF) America.

Shah, R. (2025, April 24). Saudi Arabia, India strengthen ties on green hydrogen... SolarQuarter.

Singh, R. (2024, May 24). India seen signing more renewable ammonia supply deals, policy clarity awaited. S&P Global Commodity Insights.